Blades of Her Own: Women, Swords, and the Battle for Agency

How Women of the Sword Defy Tradition and Forge Their Own Power.

"I met a lady in the meads,

Full beautiful—a faery's child,

Her hair was long, her foot was light,

And her eyes were wild." — John Keats, La Belle Dame sans Merci

Women have long been made manifest as allegories for male creation. Used to evoke a sense of ownership, artistic endeavour, or to garner support for the ‘motherland’, the history of men is often guided by the form of the female. Throughout history, male narratives have been shaped, and sometimes justified, by the female form. We see this in art, literature, and politics. From the nurturing figure of the Virgin Mary to personifications of nations like Britannia or Marianne, the feminine has often been invoked to represent purity, virtue, and a higher ideal for men to protect or dominate. However, this symbolic power often strips women of their own agency, reducing them to mere vessels for male narratives. In myths and legends, when women do exhibit agency, they are frequently cast as harbingers of death and destruction (e.g., Grendel's mother from Beowulf, the Sphinx from Egyptian mythology, and the Banshees or Baba Yaga in European folklore). Patriarchal mythologies have historically positioned them as 'other,' something to be feared, domesticated, or violently controlled, and this often done so via the taking up of arms: in particular, the sword.

Myth and Masculinity: The Sword as a Symbol of Control

A recurring symbol of male dominance in these narratives is the sword—a deeply phallic object (admittedly a Freudian interpretation, but with good reason!). The sword has long represented the power of men, not only as a weapon of war but as an extension of masculine control over both people and nature. Forged from materials mined and shaped by men, it is created through labour-intensive processes—refined in the fire by blacksmiths, wielded with strength, and honed to lethality. Its phallic nature is underscored by its being worn at the hip, always ready to serve as an extension of a man’s will. It is an object that signifies a man’s role as a warrior, protector, or conqueror—whether he fights for personal honour or for the ‘motherland.’ The sword’s ability to cut down enemies, and lay waste to landscapes, symbolises this masculine might over both men and nature.

“Then Merlin led the king by the arm until they came to a lake, the which was a fair water and broad. And in the midst of the lake Arthur was ware of an arm clothed in white samite, that held a fair sword in that hand. ‘Lo,’ said Merlin, ‘yonder is that sword that I spake of.’” — Thomas Malory, Le Morte d'Arthur

This is evident in Arthurian legend, where King Arthur's legitimacy as a ruler is literally bestowed through his ability to pull a sword from the stone—a divine symbol of kingship and power. The sword Excalibur represents Arthur’s supernatural authority over both his kingdom and his enemies. Similarly, in the Song of Roland, Roland receives the sword Durendal from Charlemagne, with the sword carrying the symbolic weight of divine right and martial prowess. In Irish mythology, the sword Caladbolg is wielded by Fergus mac Róich and has the power to cleave hills, a metaphor for its wielder’s supernatural strength over the forces of the earth. In these stories, the sword is more than a weapon—it is a representation of control over the environment and the people within it.

This control extends into modern retellings, such as Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings, where Aragorn wields the reforged sword Andúril to defeat evil and claim his role as the leader of men. The same motif carries through to the science fiction realm, as seen in Star Wars, where Luke Skywalker inherits a lightsaber as part of his journey to becoming a Jedi. The lightsaber, a rigid weapon that bursts to attention acts as a symbol of the hero’s connection to his destiny. The parallels to Arthurian legend are unmistakable.

In contrast, women in these stories are often relegated to passive roles—figures who must be protected or fought for, reinforcing the masculine archetype of the warrior-saviour. This dynamic not only serves to glorify male power but also diminishes women’s agency, casting them as objects of protection rather than active participants in their own fate. Susan Sontag, in her analysis of gender roles, further explores this phenomenon, arguing that women are frequently infantilized in cultural narratives, trapped in a perpetual state of vulnerability akin to childhood. In this way, women are positioned as dependent on male guardianship, needing protection rather than possessing the power to protect themselves. This infantilization feeds into a larger patriarchal system where women, like children, are seen as passive, needing to be controlled and shielded by men. This notion not only upholds the male warrior narrative but also confines women to roles where they lack agency.

Dominion Over Nature: The Sword as a Tool of Patriarchal Control

In Arthurian legend, swords are far more than weapons—they're symbols of authority, status, and, quite frankly, a display of masculine power. The sword, especially in the case of Excalibur, goes beyond simple battlefield utility to represent control over both people and land. In one version of the story, when Arthur pulls the sword from the stone, it’s not just about proving his worth as king—it’s about mastering nature itself. He’s literally pulling power from the earth to claim his right to rule, a metaphor for man’s dominance over the natural world and society.

Ecofeminism helps us unpack this. At its core, it critiques how patriarchal societies tend to treat both women and nature as resources to be exploited, controlled, and subdued. “Mother Nature,” after all, has long been gendered female, tied to ideas of fertility, creation, and life-giving power—mirroring traditional roles assigned to women. Patriarchal narratives, from mythology to modern industry, reflect this desire to dominate both. And what better symbol of that domination than a sword—a tool of war and conquest?

In Arthurian tales, the sword embodies this masculine drive to control. It’s not just a shiny object passed down by divine forces; it’s a means of asserting power over the land and maintaining that control through force. Even in legends outside Arthurian lore, such as the Irish myth of Caladbolg, the sword’s destructive capacity is often exaggerated to symbolise man’s might over nature itself. Caladbolg, for example, is said to be so powerful that it can cleave the tops off hills. It’s a weapon that can reshape the landscape, turning nature into something subjugated, much like the exploitation of land for agriculture or industrial gain.

Let’s take a more contemporary example: Aragorn from The Lord of the Rings. His sword, Andúril, reforged from the shards of Narsil, symbolises his destiny to lead and restore order. It’s not just about winning battles—it’s about reclaiming authority over the land, people, and even nature itself. The sword is tied to his role as protector of Middle-earth, a land that, much like “Mother Earth,” needs to be saved. His masculinity is tied to his ability to wield this weapon and conquer evil, a narrative that continues the tradition of male figures asserting control over both society and nature. This is shockingly reminiscent of the legend of Nothung (or Gram), the sword of the hero Sigurd (or Siegfried) in the Völsunga Saga and the Nibelungenlied. Sigurd’s sword was originally shattered by the god Odin, and the fragments were passed down to Sigurd, who had them reforged into a powerful new blade. Nothung is used by Sigurd to slay the dragon Fafnir, marking his rise as a legendary hero. The sword represents Sigurd’s destiny and the fulfilment of a family legacy tied to both divine and heroic power.

Ecofeminist thinkers argue that this patriarchal urge to dominate nature parallels how societies have historically treated women. Just as men seek to conquer and control the earth, women have often been viewed as passive entities—resources to be tamed, cultivated, and controlled. Swords like Excalibur and Caladbolg don’t just represent the ability to cut down enemies; they symbolise the capacity to “tame” the wilds, to turn natural chaos into something that serves man’s purposes.

Ecofeminism challenges this narrative by advocating for a more harmonious relationship with nature, one based on respect and stewardship rather than domination. It critiques the way patriarchal cultures have historically exploited both the earth and women, reducing them to resources to be controlled for economic gain or political power. In the same way that the sword in Arthurian legend is used to conquer and control, men have sought to control women’s bodies, roles, and rights. The ecofeminist perspective argues for a shift in how we view both nature and women—not as passive entities to be tamed, but as active forces in their own right.

One way in which women and female characters have done so is by taking up the sword in their own right. But what does it mean when women assume this traditionally masculine symbol? Is this just an adoption of patriarchal modes of control for individual feminist goals? Or in appropriating the sword, does the narrative inherently change?

Reclaiming Power: Women Who Wield the Sword

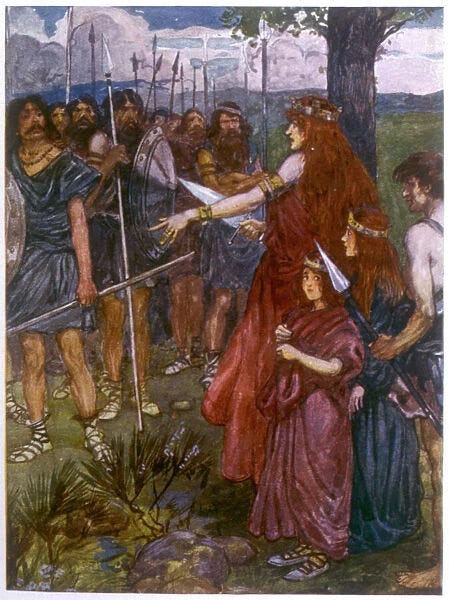

The act of wielding a sword has long been associated with power, authority, and dominance—traits often ascribed to masculinity. However, when women like Joan of Arc and Boudica take up arms, they transcend mere imitation of masculine power, asserting their own agency and challenging the societal norms that seek to confine them.

Joan of Arc, perhaps one of the most famous examples of a woman who took up the sword, led French troops against the English during the Hundred Years' War. Donning armour and wielding a sword as she claimed divine guidance, Joan’s actions were revolutionary; they not only challenged the gender norms of her time but also positioned her as a leader in a male-dominated society. Her commitment to her cause, even in the face of death, illustrates that taking up the sword is not just an act of adopting masculinity but rather an assertion of agency, a refusal to be subjugated or silenced. Joan's legacy continues to inspire feminists today, illustrating that the sword can symbolise both struggle and empowerment for women. Similarly, Boudica, the fierce queen of the Iceni tribe, led a rebellion against Roman forces in ancient Britain. Her iconic stance against oppression is not merely an act of adopting masculinity; it embodies a profound feminist rebellion. Boudica’s choice to fight for her people after suffering personal loss—from the death of her husband to the rape of her daughters—highlights her as a symbol of resistance against colonial domination. Her sword, wielded in battle, becomes a powerful representation of defiance and sovereignty rather than an endorsement of male authority. Boudica challenges the notion that power must be wielded solely by men, instead asserting that women can be fierce leaders and warriors in their own right.

Moving from historical figures to the realm of fiction, we find Éowyn in The Lord of the Rings, who embodies the spirit of a warrior defying gender expectations. Disguising herself as a man to fight alongside her fellow warriors, Éowyn demonstrates that courage and strength are not inherently masculine traits. In fact, it is her womanhood that allows her to deal the striking blow against an ‘unkillable’ enemy: Declaring “I am no man!” Eowyn finds in her femininity the ability to kill the Witchking, of whom ‘no man can kill’. In claiming her identity and proving her worth in battle, Éowyn reclaims the sword as a symbol of female empowerment rather than a tool of masculine domination. She transforms what is typically a phallic symbol of war into an emblem of her uniquely feminine strength.

While it’s easy to view these women through a lens of masculine appropriation, such a perspective underestimates their transformative impact. When Joan, Boudica, and Éowyn take up swords, they are not simply mirroring masculine power; they are redefining it. These women challenge the notion that strength is exclusive to men and assert that the sword, traditionally a symbol of male dominance, can also be a tool of female empowerment.

The significance of women adopting this symbol lies in their ability to reframe its meaning. The sword, in their hands, becomes an emblem of courage, defiance, and autonomy rather than an endorsement of patriarchal violence. By taking up arms, these women carve out a space for themselves within the narrative of power, transforming what was once an exclusively masculine realm into one that includes their strength and agency. Ultimately, the act of wielding a sword by women such as Joan of Arc, Boudica, and Éowyn signifies more than a rejection of femininity; it is a powerful assertion of their right to exist as full, complex beings capable of fighting for their beliefs and communities. This reclamation of the sword as a feminist symbol invites a broader conversation about the ways in which women can redefine power and agency, reminding us that strength and courage come in many forms, transcending the confines of gender.

Beyond Violence: Feminine Authority and the Symbolic Sword

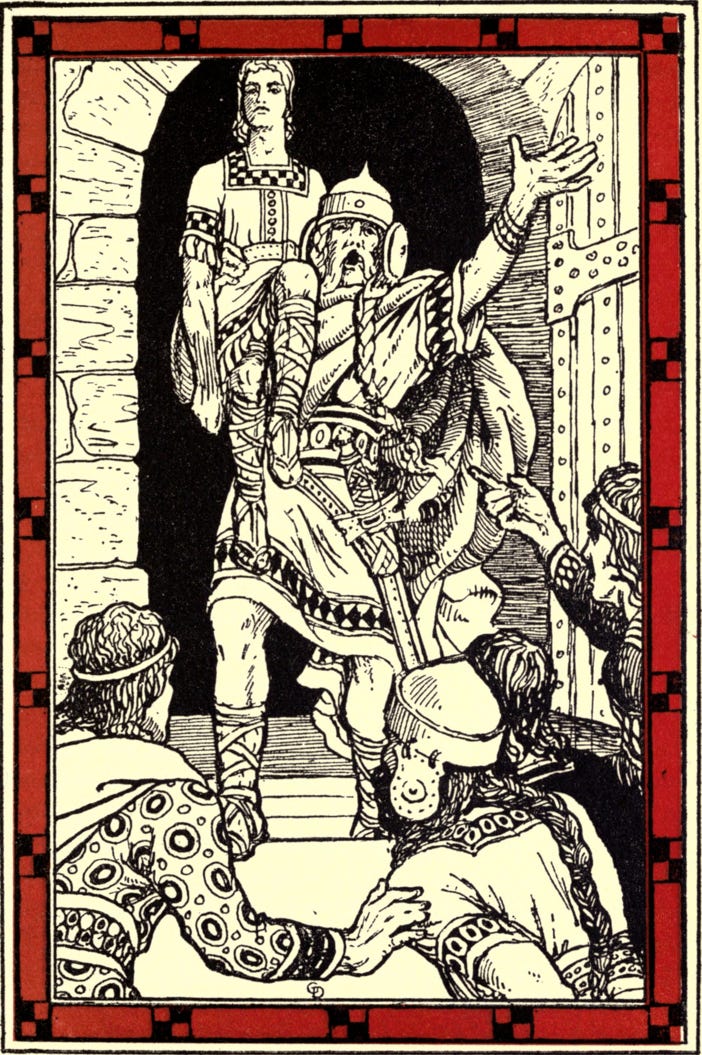

However, not all women in fictional and legendary histories wield swords in the conventional sense. Consider figures like the Lady of the Lake, who, while never directly taking up a sword, famously holds authority over one.

“And there came an arm and a hand above the water, and took it and clutched it, and shook it thrice and brandished; and then vanished away the hand with the sword into the water.” — Thomas Malory, Le Morte d'Arthur

In this iconic moment, the Lady of the Lake presents Excalibur to Arthur, an act that grants him the power to claim his rightful role as king and leader of England. Her authority in bestowing this right fundamentally alters our perception of her: she wields control over Arthur’s destiny, elevating her role from a mere background character to a pivotal force in the narrative. The Lady of the Lake exemplifies how feminine power can manifest through the act of bestowal, positioning her as a crucial agent of change within the mythos.

Another example is Brünnhilde from Norse mythology, particularly as portrayed in the Völsunga Saga and Richard Wagner's Ring Cycle operas. Although she is a warrior maiden (a Valkyrie) and associated with combat, her power over fate and the lives of warriors is far more significant than her use of a sword for violence. In Wagner’s Ring Cycle, Brünnhilde's sword-related influence is primarily one of guidance and protection. She does not wield the sword in battle herself but directs who is worthy of victory or death, thereby shaping the course of history. She famously aids the hero Siegfried by giving him essential guidance and knowledge that help him in battle, though she herself refrains from direct violence.

Brünnhilde’s influence comes from her connection to destiny and justice rather than from actively wielding the sword. This aligns with the theme of powerful women who shape events and empower others without needing to engage in violence themselves. Like the Lady of the Lake, her authority lies in her wisdom and her role as a mediator of fate.

Redefined Power: Women, Swords, and the Shift in Symbolism

In conclusion, the relationship between women and the sword, particularly in patriarchal narratives, offers a complex reflection of power dynamics in both myth and history. Traditionally, the sword symbolises masculine authority, a tool of control over land, people, and nature. Yet when women take up this emblem, they challenge the very foundations of this dominance. Figures like Joan of Arc, Boudica, and Éowyn demonstrate how the sword, a symbol of male conquest, can be transformed into an instrument of female empowerment and resistance. By wielding the sword, they do more than adopt masculine traits; they redefine power, asserting that strength and agency are not bound by gender.

Furthermore, women like the Lady of the Lake and Brünnhilde, who wields authority without direct violence, remind us that power comes in various forms—sometimes through bestowal, guidance, or influence. This reimagining of female power in relation to the sword calls into question the binary roles of protector and protected, conqueror and conquered, and instead presents women as active participants in shaping their own destinies and the world around them.

Ultimately, the appropriation of the sword by women throughout history and legend not only disrupts traditional narratives of masculine control but also expands the understanding of power. It underscores the fact that strength and agency can be wielded in myriad ways, transcending patriarchal symbols to reflect a more inclusive and dynamic vision of leadership and autonomy. In reinterpreting these symbols, women reclaim their space in history, mythology, and culture, proving that their voices and actions are as pivotal as any male warrior’s.