Don’t Turn Your Brain Off: Why Critical Thinking About Media Matters

How Anti-Intellectual Trends Harm Us.

I thrive on engaging with literature, film, and cultural pursuits that challenge me, push me out of my comfort zone, and compel me to think deeply. These experiences are non-negotiable for me, and I won’t downplay their significance for the sake of internet neutrality.

Some of the most enriching moments of my life have been spent immersed in conversations about a film, book, or piece of art- unraveling a creator’s intentions, exploring their influences, and analysing the layers of meaning, both intentional and subconscious, woven into their work.

Conversely, media (particularly literature) that fails to challenge me leaves me utterly disinterested. If a story doesn’t demand my full attention and reward that investment with depth and meaning, I rarely make it to the end. I crave narratives that make me work for their rewards, leaving me with something substantial and lasting by the time the final page is turned or the credits roll.

And honestly, I don’t think there’s anything wrong with that.

The Rise of Anti-Intellectual Trends

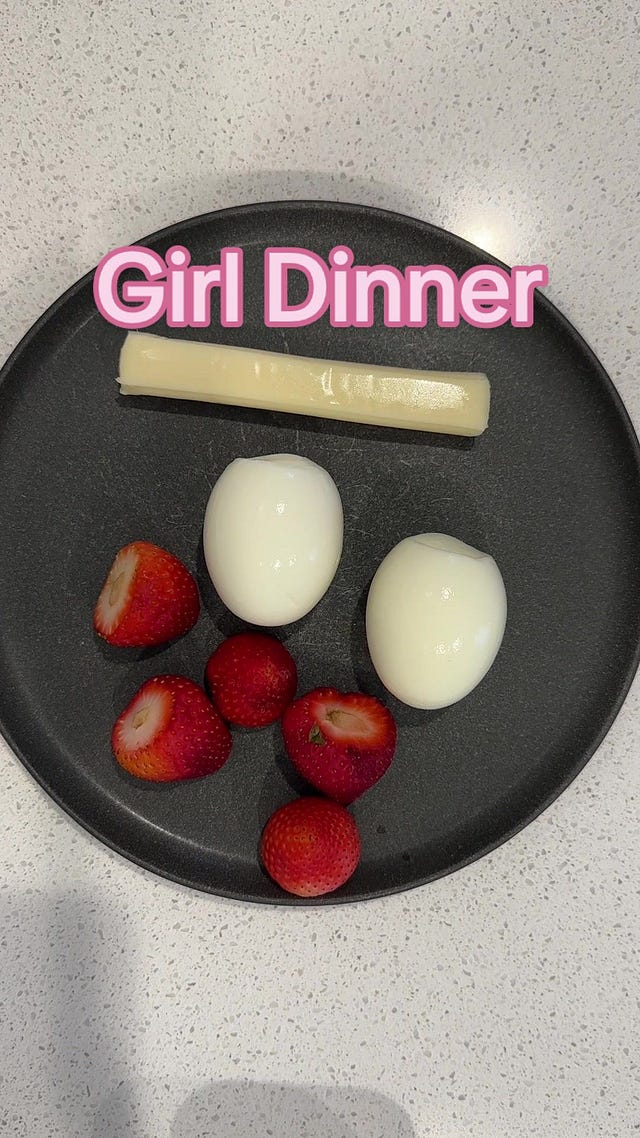

This is part of why I’ve been so unsettled by the culture of anti-intellectualism brewing online these days, especially when it comes to women. Infantilising and reductive narratives have been flooding the zeitgeist, wrapped in seemingly harmless trends and catchphrases. No doubt you’ve heard “It’s not that serious.” “Let’s not make it political.” “Girl- (dinner/math).” “My silly little humanities degree.”

These phrases might seem lighthearted, but they subtly and insidiously place women and their pursuits and capabilities into small, non-critical roles. They tell us that our intellectual pursuits, our critical engagement with the world, and even our basic autonomous choices are frivolous, unserious, and inherently tied to gendered notions of simplicity and ‘silliness’. This mindset not only limits how women and young girls perceive themselves, but also actively undermines progresses made by generations of feminists who have fought for access to education and intellectual recognition, as well as financial and political freedoms.

Why Girl Math Isn’t Just Fun and Games

Trends like “Girl Dinner” and “Girl math” reduce women’s choices and behaviours to quirky, shallow stereotypes. “Girl dinner” transforms the act of eating into a caricature of scraps and snacks, suggesting that women’s needs are inherently unserious. Additionally, this type of eating supports the concept that women don’t, or perhaps shouldn’t eat a lot of food- that restricting is a default aspect of womanhood.

Tiktok failed to load.

Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

“Girl math” additionally trivialises financial decisions, making light of women’s understanding of economics. Popularised on TikTok over the summer of 2024, “Girl Math” perpetuates "free money" logic, where returning an item is seen as free money to spend again; it is when paying with cash means that the purchase is essentially “free” since the money isn't immediately visible leaving a bank account; and it is when prepaid expenses, like concert tickets or vacations, don’t feel like real spending when the event finally arrives, creating the illusion of a free experience (amongst many others).

What is so egregious to me about this particular trend is the infantilising nature of it: the equating of ‘girlhood’ to anti-intellectual and childlike financial decisions. Many who perpetuate this trend may not realise that the fight for women's financial freedom is shockingly recent and remains ongoing in many parts of the world. For example, it wasn’t until the 1960s and 1970s in the U.S. that women were legally required to be paid the same as their male counterparts (The Equal Pay Act of 1963), and that if they became pregnant, couldn’t be fired on the spot (Pregnancy Discrimination Act of 1978). Additionally, it wasn’t until 1975 in the United Kingdom that women could open their own bank accounts without a male co-signer, meaning for the 20 or so (plus) years that women had been actively employed in the workforce, they would have to rely on a father or husband to ‘give permission’ for them to have access to their own money. Additionally, it was also only in 1974 that the Equal Credit Opportunity Act (ECOA) in the U.S. made it illegal for banks to discriminate based on gender or marital status. This landmark law allowed women for the first time to obtain credit cards and loans in their own name. This also led to women’s legal right, for the first time, to sign leases and rent apartments without needing a male guarantor. Before these hard-won victories of second-wave feminists, women had little to no control over their finances, significantly limiting their autonomy and personal freedom.

Without financial autonomy, women are effectively trapped in a childlike state, unable to work toward their goals nor escape dangerous situations such as domestic abuse. Imagine being an adult and needing permission from a male partner or family member to access your own money. What’s even more shocking is how recent these legal strides have been: many of these rights were secured less than 50 years ago- less than a single lifetime.

In perpetuating the notion that “girl math” = bad financial decisions, we unconsciously tie womanhood to financial insecurities that were considered fact for hundreds of years: ‘facts’ that allowed men to control women’s choices and freedoms. When we embrace “girl math” and “girl dinner” without question, we risk perpetuating the same old narrative: that women are inherently less serious, less capable, and less deserving of equality.

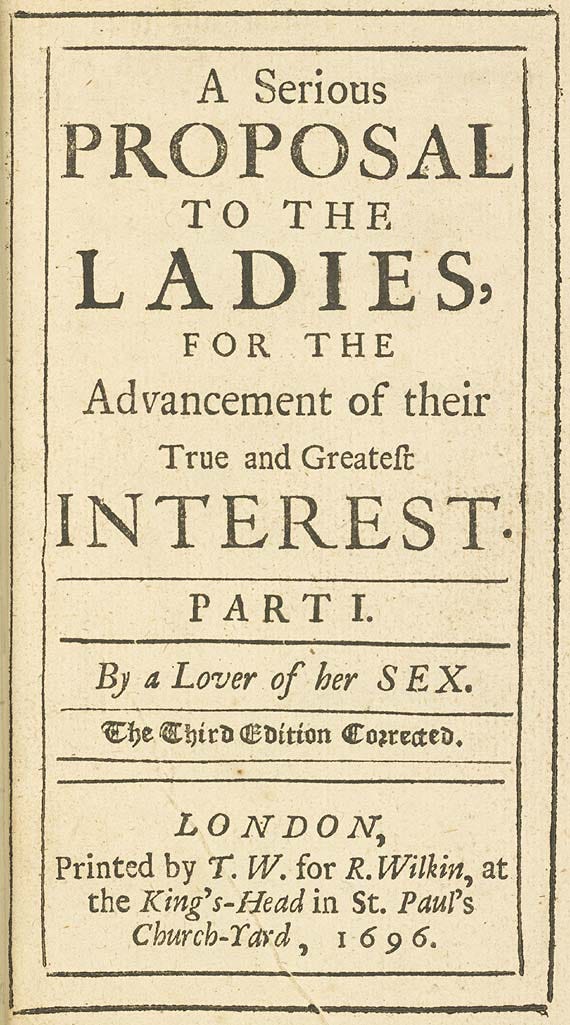

Defending the Humanities: More Than a ‘Silly Degree’

This phrase, in particular, infuriates me. If you’ve read any of my previous work, you’ll know how passionately I care about the Humanities. I think these qualifications make highly critical, research driven, argumentative scholars, who have an increasingly important role to play in our current socio-political climate.

The phrase “Silly little Humanities degree”, in a painfully self-deprecating (and sexist) way, exemplifies the current cultural devaluation of the humanities. In ‘feminising’ the Humanities, and ‘masculinising’ STEM subjects, we have seen a deepening divide that perpetuates harmful stereotypes and undermines the value of both fields. By framing the humanities as "soft," emotional, or impractical, and STEM as "hard," logical, and inherently superior, we reinforce outdated gender norms. This dichotomy not only discourages men from exploring the humanities but also subtly delegitimises the vital contributions these disciplines make to society-critical thinking, ethical reasoning, cultural understanding, and creativity. In turn, women pursuing STEM fields often face the opposite stereotype, battling assumptions that their presence is unusual or exceptional.

This polarisation ultimately harms everyone, as it narrows our collective capacity for interdisciplinary innovation and mutual respect. It also aligns disturbingly well with the broader societal shift toward mass-consumerism and the prioritisation of capitalist goals as the sole markers of success or value. The humanities, with their focus on understanding the human condition, fostering empathy, and exploring complex ethical questions, are dismissed as "wishy-washy" or impractical. This pervasive narrative suggests that pursuing an arts education is a poor investment simply because it doesn’t guarantee immediate financial return- as if money is the only logical or valid reason to seek higher education.

By equating a degree’s worth solely with its earning potential, we risk creating a society that values productivity over humanity, profit over purpose, and efficiency over empathy. This approach not only dismisses the essential skills and insights gained from the humanities but also limits our ability to address the complex, multifaceted challenges of the modern world; challenges that require both technical expertise and a deep understanding of human behaviour, ethics, and culture.

In perpetuating this stereotype we also undermine years of activism, where women have had to fight just for a seat in the room ((in the case of Anna Maria van Schurman, gaining it, but having to remain behind a curtain during her attendance - see: Martine van Elk, Early Modern Women’s Writing: Domesticity, Privacy, and the Public Sphere in England and the Dutch Republic (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2017), 185)). Figures like Elizabeth Blackwell, the first woman to earn a medical degree in the U.S., faced ridicule and hostility because her education was seen as a waste of resources better spent on men. (For further reading, I highly suggest Regan Penaluna’s How to Think Like a Woman).

Additionally, women entering universities in the late 19th and early 20th centuries were often funnelled into “acceptable” fields like teaching or literature; fields that were subsequently, ironically, devalued because of their association with women.

By calling our arts and humanities degrees 'silly,' we internalise the same dismissive attitudes historically used to deny women intellectual and professional advancement, while also perpetuating sexist concepts tied to overconsumption and late-stage capitalism.

Is It Just a Joke? Spoiler: It’s Not

These phrases are among the most insidious anti-intellectual statements circulating today. They dismiss the inherent complexity and significance of what we consume and create, as though anything could exist outside the realms of politics, society, or culture. The truth is, everything we engage with -whether it’s a blockbuster film, a niche novel, or even fairy porn- is inevitably shaped by, and reflects, the political and cultural forces of its time. Every piece of media upholds, challenges, or reframes certain ideals, values, and assumptions. No one creates in a vacuum, completely untouched by the world around them. Even the most fantastical stories carry with them the fingerprints of their creators’ environments and experiences.

By throwing out phrases like “it’s not that serious” or diminishing arts and humanities degrees, we perpetuate the idea that critically analysing media or culture is somehow unnecessary, elitist, or even undesirable. We dismiss the idea that art, entertainment, and narratives shape our worldviews and are shaped by them in turn. Worse, we imply that questioning the status quo or exploring the deeper meanings behind the things we enjoy is overreacting, something unbecoming, as though engaging intellectually with culture is only for the "too-serious" or "overly dramatic." This attitude not only diminishes the value of critical thought but also reinforces a culture of complacency, where challenging societal norms or digging into uncomfortable truths is seen as overbearing rather than vital.

No one is immune to the influences of the world around them.

At its core, this rhetoric silences curiosity and critique, encouraging people to accept surface-level interpretations and disengage from meaningful conversations about the power of media and culture. It is an invitation to look away from systemic issues, to stop asking why certain tropes, narratives, or portrayals dominate, and to dismiss those who do ask as taking things "too seriously." This resistance to intellectual engagement not only stifles progress but also allows harmful ideologies to persist unchecked, cloaked in the guise of entertainment or escapism.

In reality, nothing we consume is "just entertainment." Every story, image, or idea we interact with contributes to a broader cultural narrative, shaping how we see the world and our place within it. Recognising this doesn’t ruin enjoyment- it deepens it, offering richer, more nuanced perspectives.

After all, questioning and understanding the world around us is not an overreaction; it’s how we grow, change, and move forward.

The Real-Life Fallout of ‘Harmless’ Trends

When we accept media uncritically, we risk internalising the narratives it perpetuates, allowing it to shape our worldview in ways we may not even recognise. Media is not just a mirror reflecting society; it’s a powerful force that moulds our perceptions, often subtly reinforcing harmful stereotypes and expectations. For example, if the stories we consume consistently tell us that women must be small, fragile and sexually available above all else, these messages seep into our understanding of ourselves and others, distorting ur concept of womanhood.

Women of all ages may subsequently feel pressured to conform to unrealistic, contradictory ideals. This pressure erodes self-esteem as we measure ourselves against impossible standards that prioritise appearance and sexual appeal over intelligence, strength, or individuality. It can lead to a fractured sense of identity, as women grapple with the disconnect between who they are and who society tells them they should be.

On a broader level, these messages influence how women view one another. Instead of fostering solidarity and mutual respect, they can create competition and judgment, as women are pitted against each other to meet these narrow ideals. This undermines collective empowerment and perpetuates division, making it harder to challenge the very systems that enforce these stereotypes.

Critical thinking acts as a safeguard against this. When we approach media with a questioning mindset, we can begin to unravel the hidden messages and biases it carries. We can identify how certain portrayals uphold patriarchal values or perpetuate harmful norms. By practicing this skill, we not only protect ourselves from uncritically absorbing these narratives but also contribute to a cultural shift that demands better representation- stories that celebrate diverse, complex, and authentic expressions of identity.

Rediscovering Depth and Agency

The antidote to this cultural infantilisation and anti-intellectualism lies in active, critical engagement: resisting the urge to “switch off” while consuming media, rejecting trends that confine us to passive, reductive roles, and embracing the intellectual depth that comes from questioning and analysing the world around us. More importantly, critical reading, viewing, and thinking are not inherent abilities- they are learned skills which can be cultivated through education, practice, and intentional engagement with thought-provoking literature, art, and history.

And these skills really matter.

They shape our ability to reflect on our own biases and strengths, to build a sense of self that is rooted in substance, and to confidently advocate for our needs and rights. They remind us that we are more than what we buy, wear, or consume: we are thinkers, creators, and change-makers- if only we choose to embrace that potential.

Ultimately, reclaiming depth and intellectual engagement is not just about resisting shallow trends or rejecting anti-intellectualism; it’s about reclaiming our humanity. The media we consume, the conversations we have, and the narratives we internalise shape our understanding of ourselves and our place in the world.

This isn’t about being “too serious” or “making everything political.” It’s about recognising the inherent politics in all things and refusing to be passive participants in a culture that seeks to define us through stereotypes and sales. It’s about holding space for complexity, valuing intellectual growth, and demanding representation that affirms our full humanity.

If we want to build a better future, one where people are valued for their ideas, their individuality, and their humanity, we have to start by rejecting the call to “turn our brains off.”

Instead, we must choose to think deeply, ask questions, and, lastly, engage fully.

This is great Brie!! I’m currently reading The Feminist Killjoy Handbook by Sara Ahmed and I feel like you’d enjoy (if you don’t already know it)

Exactly! I didn't work my arse off for my first-class degree to be called "a silly little humanities subject" and with what appears to be a reduction in media literacy and an influx of "fake news", humanities are so important right now! Great work loved this! X