Heads Will Roll: Women, Power, and Severed Heads in Art History

Severed Heads and Silent Grief... Women, Power, and the Art of Beheading

The Severed Head- a Feminist Symbol?

"O Lord, God of my father Simeon, into whose hand You gave a sword to take vengeance upon strangers who had loosed a virgin’s girdle to her shame, and uncovered her thigh to her reproach... so do You, O Lord of Heaven and Earth, give me strength this day." (Judith 9:2-11)

A beheading is an intrinsically violent, reproachfully gory thing to behold. The strength necessary, both physically and mentally, to bring that blade down upon another neck—the crunch of the spine, the snapping of ligaments and cartilage. Yet, throughout art history, many women have been depicted as taking on such a task. Inspired by religious texts, such as the Book of Judith, or literary characters like Isabella in Keats’ Isabella and the Pot of Basil, women have utilised the cleaving of heads from men's shoulders for their own ends. It is such a popular trope within the fine art field that I can bet that if you wander through any Western art gallery, you are bound to see at least one depiction of such a female figure.

For something that feels in some ways to be a ‘You go girl’ moment, there also underlies a sense of male fear, and perhaps a pseudo femme-fatale that has been used against women through the ages. So, what are these characters' stories? Are they ones of power, justice, and vengeance, or lost love? And how does that convey control within such transhistorical settings?

Judith and Holofernes: The Ultimate Femme Fatale

Judith has become an archetypal figure in art and literature because she embodies female agency and empowerment in a male-dominated context. Her story, where she decapitates the Assyrian general Holofernes, presents a rare instance of a woman taking control through violence- something traditionally associated with men. Unlike passive female figures, Judith is active and strategic, making her a potent symbol of autonomy. Her use of beauty and cunning to seduce and kill Holofernes also brings a moral ambiguity to her character—she is both virtuous and manipulative, making her intriguing and open to various interpretations. This complexity allows her to transcend simple categorisation, which is why she has fascinated artists and writers for centuries.

“You're killing people?”

“No. I'm killing boys.”

-Needy to Jennifer in ‘Jennifer’s Body’ (2009).

Judith’s role as a symbol of divine justice and resistance further enhances her archetypal status. She acts on behalf of her oppressed people, making her story one of liberation and rebellion against tyranny, which resonates in times of social or political struggle. Additionally, the image of a woman holding a severed man’s head disrupts traditional gender roles and power dynamics, tapping into deep cultural anxieties about female power. From Renaissance depictions to modern feminist reinterpretations, Judith’s story has provided artists with a powerful motif to explore gender, power, and violence, ensuring her lasting relevance as a symbol of both transgression and strength.

This act has been depicted by artists across many generations. However, two key figures from the Baroque have come to represent this original femme fatale: Artemisia Gentileschi with her two paintings of Judith Beheading Holofernes (1620-21 and 1611-12), and Caravaggio with Judith Beheading Holofernes (c. 1598–1599).

Looking at these two works, ask yourself first: Which Judith seems the most engaged with the task she is undertaking? Who shows the most agency? Why?

If you’re like me, you will have identified Gentileschi’s work as the one in which Judith is depicted with the most active agency. She is bent towards the act, her arms strong, pressing the sword against Holofernes throat. Her look is one of determination, even as blood gushes from the killing wound. While Caravaggio still depicts a strong Judith, there is something lacking in her stance and the distance she puts between herself and Holofernes. Her limbs remain soft, the skin subtle, and her face betrays her squeamishness.

Within a feminist framework, many art historians have claimed that Gentileschi’s depiction is one informed by her gender as a female artist, particularly one who experienced sexual assault and rape. We might read into this gruesome depiction of a beheading the rightful justice, or perhaps simply vengeance, of a woman scorned in her own time; a sort of feminist revenge flick (a la Quentin Tarantino). Because yes, this act is inherently violent. It is gory. It is destructive and disgusting.

Yet, it is also powerful: it requires power to enact, and bestows power in its acting. In taking his life, Judith is reclaiming her personhood and acting in such a way that represents her goals, desires, and needs. In removing one life, she restates her own.

Grief Grown in Earth: The Poetics of Isabella’s Mourning

So, what about women with the heads of men they loved, instead of hated? In Keats’ Isabella and the Pot of Basil, such archetypal depictions are made into a story of love lost.

In the poem, Isabella and Lorenzo fall deeply in love, but her brothers, driven by greed and family honour, disapprove of the match. They murder Lorenzo, bury his body in a remote forest, and deceive Isabella about his fate. In despair, Isabella has a dream where Lorenzo’s ghost reveals the truth and the location of his grave. Grief-stricken, she finds his body, and unable to carry it in its entirety, decapitates him, and hides the head in a pot of basil, where she tends to it with obsessive devotion. Her brothers, noticing her strange behaviour and the flourishing plant, eventually discover the hidden head and take it away, leaving Isabella to die of sorrow.

During the late 18th and early 19th centuries, England was undergoing significant economic changes due to the Industrial Revolution. This period saw a growing gap between the rich and the poor, with an emerging capitalist economy reinforcing rigid class divisions. Isabella reflects these class tensions, as her brothers murder Lorenzo to protect their family’s wealth and status. The story critiques the dehumanising effects of greed and social ambition, which sacrifice genuine love and human connection for material gain. The early 19th century also saw a revival of interest in Gothic literature, with its focus on the macabre, the supernatural, and psychological extremes. Keats drew from Gothic traditions in Isabella, with the haunting image of Lorenzo’s ghost and Isabella’s morbid devotion to his severed head. The Gothic elements of the poem align with a cultural fascination with death, mourning, and the darker side of human emotions, which were prevalent in literature at the time.

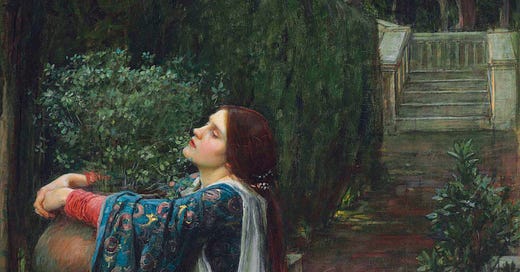

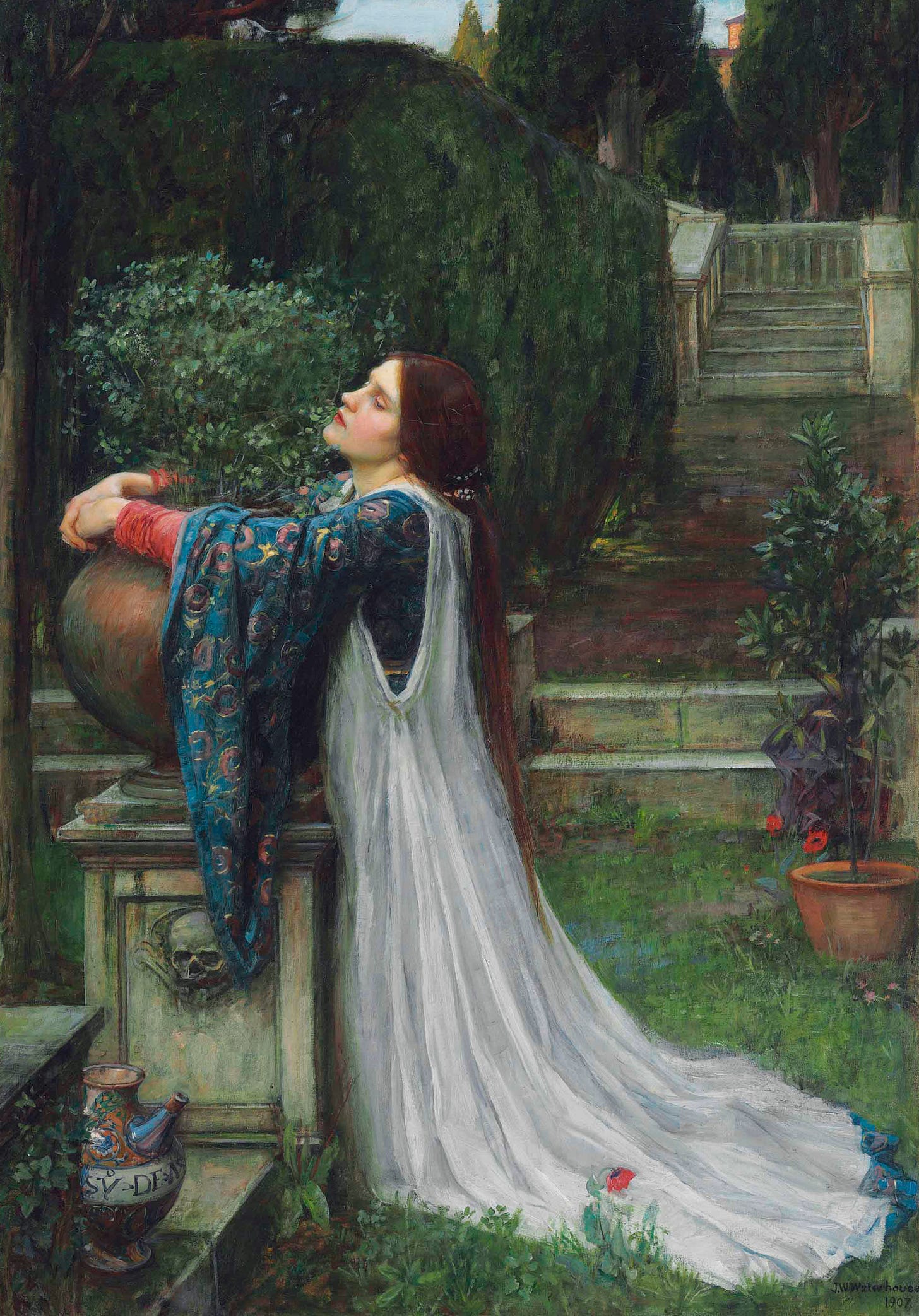

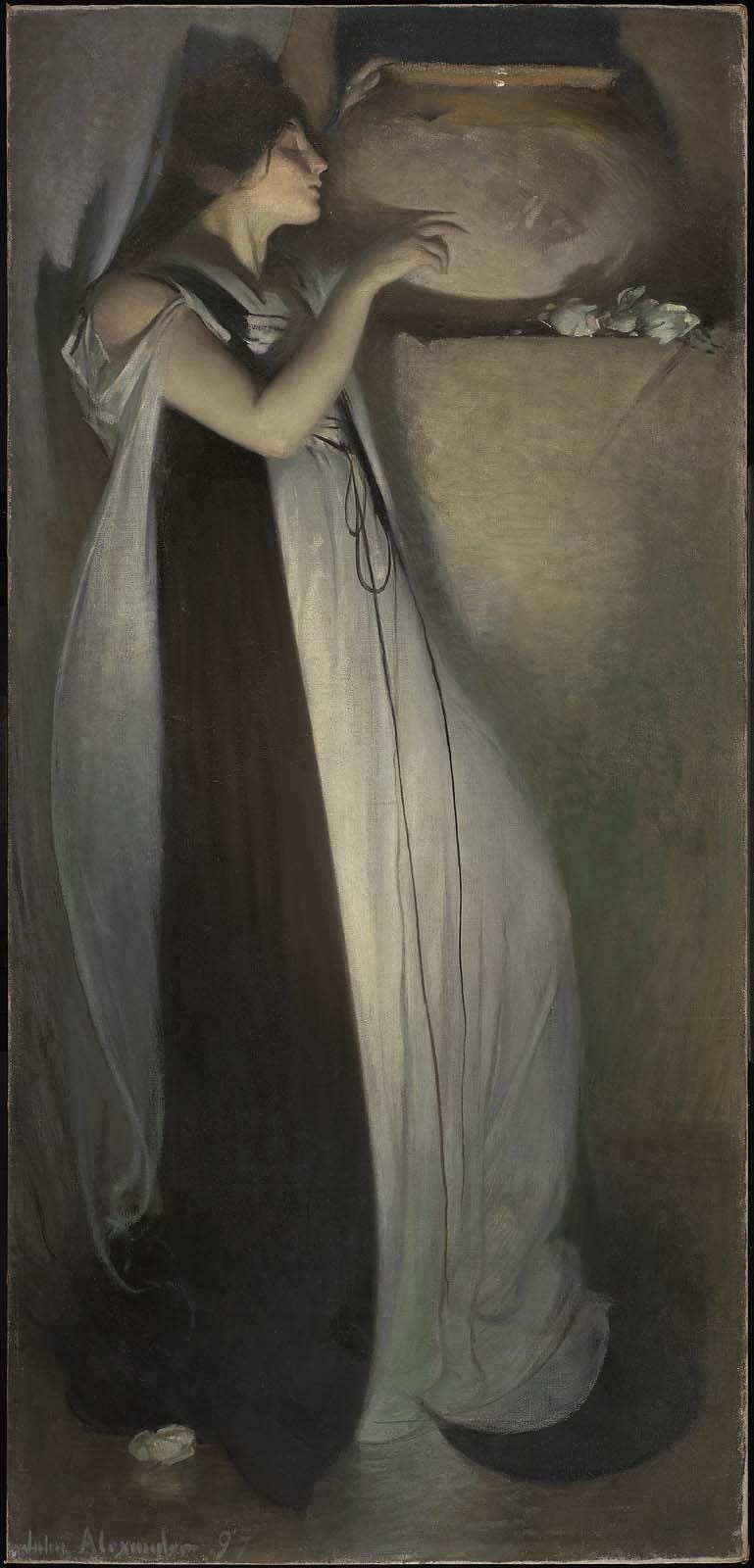

This tale of love and loss was depicted by artists throughout the mid to late 19th century, with particular attention given to the tale by Pre-Raphaelite artists. One of the most famous depictions is by William Holman Hunt, a founding member of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, who painted a highly detailed and emotionally charged version of the poem. In this work, Isabella is shown cradling the pot of basil, her face filled with sorrow, while the plant blooms with vitality. Hunt’s painting emphasises her macabre, obsessive love and grief, using rich colours and intricate details characteristic of the Pre-Raphaelite style. The pot itself is the central symbol in the painting, which is underscored by the inclusion of a skull at its circumference, drawing attention to its deathly passenger.

Pre-Raphaelites were obsessed with symbolic iconography, and this painting is no different. The flourishing basil symbolises the continuation of life through death, as well as the deep connection between love, memory, and loss. The way Isabella too rests her head on the basil pot, her hair folding into the plant itself, suggests a merging of herself with her lost love, symbolising how her identity has become entirely bound up with her mourning. Additionally, the Pre-Raphaelites were obsessed with the Victorian concept of the language of flowers. The disembodied rose cast to the ground, once a symbol for love, echoes the fate of this connection: Both metaphorically (love having died) and literally (the ‘head’ of the rose cut from it’s body, it’s own kind of beheading). By centring the narrative around these iconographic symbols, the Pre-Raphaelites could explore themes of eternal love, memory, and devotion without delving into the violent act that precipitated them.

Though the violence of the beheading is purposefully hidden behind the beautiful nature of the work, we still see a woman in immense, overwhelming mourning: grief so great that she used her own tools to take the head of her lover from his shallow grave back to her home. The violence, disgust, and horror of this act are neutralised in these depictions, but when you know the story, you can read into the heavy emotionality of such a tale.

Given the history of Judith’s depictions, it raises the question: why didn’t the Pre-Raphaelites depict the act of the beheading? Why is the silent, nun-like contemplation of loss a better narrative than the grief-stricken removal, carrying, and planting of the head? Well, the Pre-Raphaelites were known for exploring the emotional and psychological states of their characters, often choosing introspective moments over explicit violence. In the case of Isabella, the artists focused on her deep mourning and obsessive devotion, which are more emotionally complex than the violent act of beheading. Depicting her tender care for the pot of basil, which holds her lover’s severed head, allows them to emphasise her grief, loss, and inner turmoil in a more poetic, reflective manner.

By avoiding the moment of Lorenzo’s murder, they could also highlight the consequences of Isabella’s love and the depth of her sorrow, aligning with their interest in capturing the emotional aftermath of tragic events rather than the action itself. The pot of basil becomes a symbol of her grief, making the psychological aspect of her mourning the focal point rather than the violent act that led to it. Lastly, the Pre-Raphaelites preferred to depict tragedy through an idealised lens, focusing on beauty and melancholy. The murder of Lorenzo, with its violent and bloody imagery, would have conflicted with their commitment to creating aesthetically beautiful works, even when dealing with sorrowful or tragic themes. Instead, by portraying Isabella with the pot of basil, they were able to capture the haunting beauty of her love and loss without disrupting their aesthetic principles.

That being said, I would personally love to see a woman’s interpretation of this narrative; the disgusting nature of grief, one that turns us into versions of ourselves we never knew possible- that version is in itself incredibly interesting to me. (Not saying the pre-raphaelites were cowards but…)

Feminine Power or Male Fear?

In the depictions of women like Judith and Isabella, we are confronted with a dual narrative: one of empowerment and another of fear. Judith, a figure who wields the sword with precision and purpose, embodies the ultimate rejection of male control, yet her story is also steeped in the anxieties men have historically projected onto women. Her violent decapitation of Holofernes is more than an act of personal or political justice—it is an affront to the patriarchal order, where women are expected to remain passive and submissive. Judith's power disrupts these expectations, provoking both admiration and deep-rooted fear. Her role as the be-header of men challenges the very foundation of male dominance, invoking a fear of female autonomy that has persisted across centuries.

In contrast, Isabella’s story adds complexity to this dynamic. Her actions are not driven by vengeance or the desire for liberation but by overwhelming grief and love. Yet, even here, we see echoes of male fear—her obsessive care for Lorenzo’s severed head hints at a woman so consumed by loss that she transcends acceptable bounds of feminine behaviour. The Pre-Raphaelites’ decision to avoid the graphic violence of Lorenzo’s beheading, instead focusing on Isabella’s tender mourning, suggests a reluctance to confront the full extent of her emotional and psychological turmoil. It is a sanitised version of female suffering, one that skirts the disturbing and raw reality of her actions.

“I’m the cunt you married. The only time you liked yourself was when you were trying to be someone this cunt might like. I’m not a quitter, I’m that cunt. I killed for you. Who else can say that?” - Amy Dunne in Gone Girl (2014)

So, is this a story of feminine power or male fear? Perhaps it is both. Judith and Isabella represent two sides of the same coin—one defined by action, the other by emotion. Both women exert a form of control over the men they behead, whether through the violent act itself or through their morbid devotion. And yet, their stories also expose the pervasive fear of what women might do when pushed beyond their socially constructed roles. By decapitating men, these women symbolically reclaim power, but they also become figures of male anxiety—women who defy their prescribed place and force a reckoning with the fragility of masculine control.

In art history, the imagery of women and severed heads has often been co-opted to reflect this fear, reducing female agency to dangerous seduction (Eve, Lilith, Salome and Medusa to name only a few) or hysterical grief (Hello Ophelia, Niobe, the Aeniad’s Dido, or even La Llorona from Mexican folklore). But when viewed through a feminist lens, we can reinterpret these figures not as warnings or threats but as symbols of resilience, strength, and self-determination- even if that takes the form of revenge. Judith’s sword and Isabella’s pot of basil become instruments of power, not just over men but over their own narratives in breaking with tradition. Whether through violent defiance or melancholic devotion, these women carve out spaces of autonomy in a world intent on suppressing them.

In the end, the question may not be whether these women represent power or fear, but whose power and whose fear we are talking about.

I want to hear your thoughts!

Do you see these depictions of women beheading men as empowering, or do they reinforce male fears of feminine power? Why?

Do you think the omission of explicit violence in depictions like Isabella and the Pot of Basil softens or enhances the emotional weight of the story?

Which modern stories or media do you think carry on the legacy of women wielding power through vengeance or grief?

Thanks for reading! I want to delve more into other representations of this theme (Medusa, Salome etc.) as well as other femme fatales from history. Keep an eye out for my future posts!

This was so interesting to read, and certainly made me want to return to my art history books. Thank you for this piece!