Last week I joined my fellow students in Utrecht to protest against proposed cuts to higher education in the Netherlands. The Right-leaning Dutch government, formed in 2024 after months of negotiation, plans to slash billions from higher education, including €215 million annually from universities and €1.1 billion from research budgets. These reforms are set to hit humanities programs particularly hard, targeting disciplines that are vital to understanding and navigating an increasingly globalised world.

At Leiden University, 36 of 51 humanities programs, including African, Asian, and Middle Eastern Studies, face closure. These are not niche or expendable areas of study; they represent crucial knowledge bases for fostering cross-cultural understanding, diplomacy, and historical awareness. Utrecht University is similarly planning to phase out six programs by 2030, including French, German, and Arabic, citing financial un-sustainability. It seems as soon as budgets get slashed, it is always the Humanities that are the first to go.

Unfortunately, this isn’t my first rodeo.

A Blow to Art History: Budget Cuts and Misguided Priorities

Back in 2019 before I completed my Honours in Art History at Victoria University of Wellington a similar event occurred. I was excited to begin learning about a topic I was fascinated by, and had found success professionally through working at various museums, when suddenly the entire Art History department was in a state of strife.

Perceived ‘un-sustainability’ of the leading program at VUW was rationalled against budgeting concerns, resulting in a proposed cut of a senior lecturer position, as well as the essential administrator role. The community rallied together against this proposed change, as the Classics and Religious Studies programs similarly faced, with some such concerns exemplified in a letter provided by the leading Art History organisation for the entirety of the Australasian region:

“Given that the School of Art History, Classics, and Religious Studies has been targeted due to a budget crisis brought about by declining numbers in all its programmes, it seems mightily unfair to punish Art History with a proposal that will cause a loss of staff and of popular courses, lead to an additional decline in student numbers, and make further staff redundancies inevitable. The strength of the program, the importance of the discipline both within the University and more broadly means there simply is no clear, defensible justification for the current proposal. The only conclusion one can reach is that the discipline has been unjustly targeted due to a misperception or complete misunderstanding of the significance of the VUW Art History programme.”

Sadly, against such strong support from the GLAM community and a well-supported petition, the program still faced its budget cuts. It was also moved from its central, beautifully converted historic offices right next to the university Gallery to the eighth floor of the rickety, leaky high rise building which had been untouched since the 80s.

This was a tough blow for the program, and reflected the growing change in direction of educational fields away from ‘theoretical’ humanities subjects to STEM based, job-creating perceived diplomas.

Painfully, again in 2023 similar proposed cuts were presented.

Perhaps not so surprisingly, the humanities were once again on the chopping block. Around 230 full time equivalent roles had been identified for redundancy as the university worked to overcome a $33 million deficit, targeting areas such as languages, secondary school teaching, tourism, management, geophysics and physical geography, with other programmes merging, and 39 general (non-academic = administrative) roles being targeted. Programmes proposed to be outright discontinued included Italian, German, Latin, Greek, Design Technology, secondary school teaching, tourism management, and physical geography. I wonder if anyone else is seeing a pattern yet?

The very fact that they were considering cutting Secondary School Teaching, the most undervalued yet ESSENTIAL profession any nation has, speaks- no, SCREAMS- to the tech-bro-ification of universities. This decision exemplifies that it’s not about employability, or providing the best opportunities for students, nor creating the best society for the next generation- it’s about money.

Fighting for the humanities has therefore been a constant in my life, finding its place in signing petitions, attending protests, and even in casual conversation. In a world so consumed by neo-liberal capitalist rhetoric, I actually assume that many probably agree with the idea that such qualifications are ‘worthless’ in this day and age. I’ve been told as much on several occasions.

“Why study languages at University? Can’t you just do that in your downtime?” or “What’s the point in having an ‘African Studies’ program? How does that result in any kind of employment? They’ll be working in Starbucks in no time, that’s for sure.”

I bet many of you reading this have heard these notions- either in person or online. I in fact recently posted about engaging with this rhetoric in my essay ‘Art History is a worthless degree…’, published to my Substack before I was made aware of these latest budget cuts. Disappointingly serendipitous now, I spoke in this essay to the role of the Humanities in shaping an inclusive, critical, and effectively democratic society.

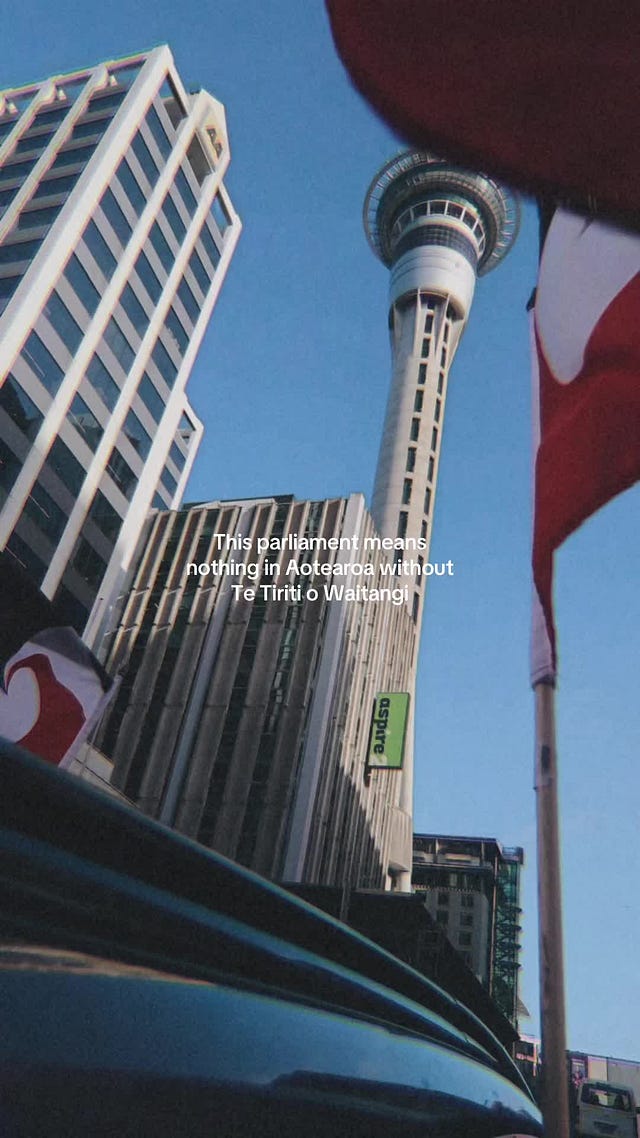

Since then, Trump has been elected President, Māori are fighting to retain their rights as established in the founding document of Aotearoa New Zealand, and we are seeing video after video of the genocidal atrocities occurring in Palestine, and the real world effects this has on people beyond those borders.

Tiktok failed to load.

Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

Now, these examples aren’t only the making of a continuous undermining of education and the humanities. I would never claim as much.

However, they are evidence of a world that is struggling to find the ability to work together: it seems lines have been superficially drawn, ‘others’ identified, vilified, and targeted- either politically or physically.

There is so much fear. So much hatred.

So many instances of the past being repeated.

And as I walked once more against budget cuts that target Humanities subjects, this time in a new country working towards a new degree, I felt a chilling sense of deja-vu.

Why the fuck am I having to do this again?

I am so tired of having to fight for the Humanities.

The Humanities: Essential Tools for an Ethical and Inclusive Society

Though established as opportunities for aristocratic offspring to gain a formal, social and cultural education, the humanities have been shaped into programmes of critical thought, argumentative writing, and research driven academia open to more and more diverse groups. Not only has there been an increase in the diversity of people who enrol in these programmes over the years, but the subject matter they engage with has also changed to reflect important social and political progressions.

In my opinion, it is through the humanities that one can learn about ethics and morality in its critical and diverse applications; because sure, you can pillage impoverished countries for raw materials to build your ugly cyber-trucks because that represents the next stage in capitalist technological progress, but no one asked if you should- if it’s ethically irresponsible…

It is only through the humanities that people can learn about the mistakes of the past, and recognise them re-occuring in our present day- hello neo-fascism filtered through American supremacist nationalism.

And, it is only through the humanities that the stories of marginalised peoples can be identified, researched, and elevated, challenging prominent thought, and building academically supported counter-cultures, such as decolonisation.

Humanities subjects are master classes in crafting the tools necessary to build a functioning, inclusive, and most importantly, empathetic society. Through languages alone students contribute to international relationships, engaging with diverse literary traditions, and preserving cultural heritage. Language is itself an incredibly important aspect of identity: ask any Irish gaelic or te reo māori speaker. Even if you choose to ignore all these important aspects, simply knowing history so we don’t repeat it must be considered of importance? Right?

I say so because this sidelining of the Humanities has been occurring in waves over the last hundred or so years, with very real effects on society.

A Historic Shift Towards Profit-Driven Education

In the 20th century, periods of intense centralisation and ideological control further deepened the marginalisation of humanities subjects. Governments, often focused on maintaining political or economic control, sought to harness education to serve specific national agendas, framing technical and scientific expertise as essential to progress while viewing the humanities as expendable.

Sounding familiar yet?

Liberal arts disciplines, with their emphasis on critical thinking and questioning dominant paradigms, were then seen as less compatible with the goals of state-driven modernisation or social engineering (especially in those countries that were led by fascist governments). This devaluation resulted in a narrowing of educational priorities, reducing the capacity of institutions to nurture diverse intellectual perspectives.

The United States, for example, has experienced a similar erosion of the humanities since the 1990s, shaped by rising tuition costs, the corporatization of universities, and a national pivot toward fields perceived as economically beneficial. Federal initiatives like the America COMPETES Act emphasised STEM education to maintain global competitiveness, while public scepticism about the "practical" value of humanities degrees led to declining enrolment in fields like English and History.

Subsequently, universities, increasingly adopting a corporate model, began prioritising programs that attracted high enrolment numbers and research funding, often at the expense of humanistic disciplines.

And this didn’t just happen in the United States: this has occurred all around the world.

This corporatization, brought on by a perceived need for profit-driven growth, has led to the marginalisation of these essential fields of study. Humanities programs, which as we have established equip students with critical thinking, ethical reasoning, and cultural literacy, have struggled to justify their relevance in an education system focused on immediate job placement and financial returns. At the same time, political polarisation has fuelled attacks on disciplines like gender studies and ethnic studies, further delegitimising the humanities in public discourse: hence the well-known online debates and jokes about baristas, unemployment and continuous study as a means of not entering the ‘real world’.

The consequences of these changes have been stark: a narrowing of educational priorities, reduced critical inquiry, and diminished societal capacity to address complex issues like systemic inequality, climate change, and cultural division.

The elimination of humanities programs in the Netherlands, and abroad, further entrenches this necro-capitalist focus on immediate economic returns over long-term societal benefits. The sidelining of African, Asian, and Middle Eastern Studies at Leiden University, for instance, reflects a dangerous prioritisation of Western-centric narratives, undermining efforts to promote equity and inclusion in education. Similarly, cutting language programs, like at Utrecht University, diminishes our capacity for global cooperation and cultural exchange.

Not only that, but as language programs are often among the first to face cuts, in doing so, the humanities become increasingly perceived as expendable. And I hope that by this point in my essay you would agree with the fact that they are, in fact, indispensable.

As policymakers prioritise STEM and technical disciplines, it is crucial to recognise the invaluable role of the Humanities in sustaining democratic institutions and addressing systemic challenges. Relegating humanistic inquiry to the margins is a shortsighted response to complex challenges.

The lessons of history are clear: a society that neglects its cultural and intellectual foundations cannot sustain itself in the long term.

The Netherlands, nay, the world, therefore has a choice to make: will it repeat the mistakes of the past, or will it recommit to the values that have shaped its intellectual and cultural identities?

Only time with tell…

If, like me, you want to reverse this trend, I’ve compiled a few ways below on how to help do so. It will require collective action, from lobbying governments for sustainable funding to reimagining how the humanities are taught and valued. And that isn’t just at the university level: it needs to go all the way back to when kids enter the schooling system for the very first time.

However, if we do not act now, the costs will be borne not just by academia but by all of us, as we face a future increasingly devoid of meaning, creativity, and critical thought.

So please, please, in whatever means you can, support the humanities!

If you’re a little lost on how, or short on time or money, these are just some examples of ways you can incorporate the support of humanities subjects into your daily lives:

1. Engage with the Arts and Literature

Read books from diverse cultures, historical periods, and genres.

Attend live performances like theatre, dance, or poetry readings.

Explore local art galleries, museums, or cultural exhibits.

2. Support Educational and Cultural Institutions

Donate to libraries, museums, or organisations that promote the humanities.

Participate in community education programs or workshops.

Advocate for arts and humanities funding in schools and public spaces.

3. Promote Conversations

Discuss history, literature, philosophy, or art with friends, family, or colleagues.

Join book clubs or attend public lectures and discussion groups.

Engage with podcasts, YouTube channels, or blogs focused on humanities topics.

4. Celebrate and Preserve Heritage

Research your own cultural or family history and share it with others.

Support cultural preservation initiatives, such as language preservation or historical landmarks.

Participate in or volunteer at local cultural festivals or heritage days.

5. Support Humanities-Based Media

Subscribe to magazines, journals, or websites that focus on culture, history, and the arts.

Share articles, videos, or events related to the humanities on social media.

Write reviews or promote authors, artists, and creators whose work contributes to the humanities.

6. Be a Conscious Consumer

Buy books, music, or artwork from independent creators.

Support local businesses or organisations that promote the arts.

Purchase memberships to museums or cultural organisations.

7. Incorporate Humanities into Daily Life

Take time to reflect on philosophical questions or engage in mindful practices.

Write, paint, or journal to explore your own creativity.

Practise or learn a new language to connect with different cultures.

8. Advocate for Policy Support

Voice your support for humanities programs in schools and universities.

Sign petitions or attend rallies for arts and humanities funding.

Communicate with policymakers to emphasise the importance of cultural initiatives.

If you’ve gotten this far, thank you for sticking with this important piece! Let me know your thoughts, and if you’ve experienced something similar in your own context.

Thank you for putting this feeling into words. It is a comfort to read this and know that while we’re tired, we are not alone.

Thanx for your thoughtful piece, Bri. It is indeed very worrying what is happening in the Netherlands and beyond. I am also vey worried about the cuts that are proposed for the NPO broadcasting cooperation. I'm enjoying many of their excellent documentaries here in NZ, online though the NPO app. The quality and variety of these programs is just mind-blowing. I just hope the Dutch voters realize in time that this government is bad news.