"A Sort of Pioneer" – A Letter to Mary Cassatt on Distance, Dedication, and Becoming

From the Margins: Women, Artistry and the Pursuit of Legacy. Part One.

This is part one of a two-part article examining the lives, work, and life writings1 of Mary Cassatt (1844–1926) and Frances Hodgkins (1869–1947)—two modern-era artists who migrated to Europe in search of artistic legacy. In doing so, their lives, letters, and art represent the lived experience of a dual peripherality: as women and as artists from the margins, they navigated, challenged, and were constrained by the gendered and national boundaries that shaped their worlds.

Influenced by Celia Paul’s ‘Letters to Gwen John’ (2022), the following text is formatted as a letter, at times hand-written, addressed directly to the Mary Cassatt from the author.

*Code for in-text citations of letters located at the bottom of the article.

Looking at this self-portrait of yours Mary (Figure 1), I see a quiet declaration. It’s a beautiful work: your use of colour in particular is a kind of chorus, discordant tones placed together to form something surprisingly harmonious. There’s a soft lilac shimmer in your whites, an almost acidic lime wash to your sage background, and deep, earthy red stripes that drip over the muddy, moss-toned sofa you’re leaning against. Your body reclines across the picture-plane, creating an asymmetry that pulls the eye. Yet you’re not necessarily relaxed, as there remains a purposefulness to your pose, conveyed through thick, unblended strikes of paint to canvas. You balance stillness with turbulence here—a ruckus of brushstrokes that reveal your hand’s embrace of the impressionist impulse.

Yet it’s the way you’ve carved out your head that draws my eye. Framed by a deep red bonnet too heavy for your airy surroundings, it’s richness of velvet, taffeta, and silk flowers cups your face in a tight bow beneath your chin, holding your face ajar. And your expression—that faraway gaze cast beyond our sight-lines—draws me in. What are you looking at? Why do you seem both composed and yet quietly uneasy?

There’s a clear tension here—your setting is unmistakably interior, yet your gaze is turned outward, toward a world beyond our reach. At the same time, your focus feels inward: hands clasped tightly to your torso, your expression revealing a mind in motion—an allegory of the artist’s intellect. Perhaps you’re reflecting on the years spent orbiting, studying, navigating the European art world from its edges, considering what led you to this moment, this style, this city: Paris. Your shifting from meeting expectations to exploring how to transcend them. An artist, a woman, mid-thought—shaping both her future and the way she wishes to be seen.

As we both know, though, you didn’t start here.

“Mary wishes to be remembered to you. She laughed when I told her your message and said she wanted to paint better than the old masters.”

- (EH to Mrs. SH, May 15, 1867).

Growing up in the United States, you began your career within a cultural “periphery.” The art world of your time was rigidly hierarchical, with Europe positioned as the central heart of Western art. All other geographic outposts of empire were thus rendered peripheral by association—a marginalisation of arts and cultures emerging from the Americas, Australasia, and Africa, each to varying degrees. The Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, where you began your training as a painter at just fifteen, reinforced this cultural divide.2 Though you were equipped with many of the tools deemed necessary for artistic success, the Academy remained a microcosm of the periphery’s gaze toward its European centre. Its instructors, all trained abroad, passed down an imported European academic tradition. Each year, the ‘blockbuster’ exhibitions that toured Philadelphia—the city of your teenage years—brought with them Old Masters and rising stars of the Parisian Salon.3 You visited these shows with your classmates, speaking of older students who had already left for Paris in search of artistic legitimacy. They enrolled at the École des Beaux-Arts (closed to women until 1897), studied in private ateliers, and exhibited at the annual Salon, their subsequent successes reported back home with vigour.

The message was unmistakably clear: true artistry lay across the Atlantic.

This peripherality must have felt suffocating for you, as even in your youth you burned with ambition, possessing a startling self-assurance that at times even got you into trouble.4 Your parents, much like my own, had raised you to think independently—your brilliant mind ultimately turning all your attention to your “passion for line and color.”5 It’s no real surprise, then, that you left your American shores for the European studio when you were twenty-two—your departure an attempt to stand in the centre’s light.

When you get the chance, Mary, I’ve sent you a quick voice-note…

And what a glorious few years those were!

You travelled through France and Italy, cultivating a web of mentors and peers—each connection strengthening your practice. Then in 1868 your breakthrough: La Mandoline (Figure 2) accepted by the Paris Salon! After what must have felt like years of striving, you'd finally arrived at art's glittering centre. Did you read Eliza Haldeman’s letter to her parents about your accomplishments? Humbly supportive, she wrote “Mary has also been successful, even more so than I, as her picture is well hung and was not painted on,” (EH to Mr. & Mrs. SH, May 8, 1868). It was common for young artists to have their works ‘corrected’ before exhibition; yet yours stood entirely on merit, even placed ‘on the line’—a prime position. For your work to be recognised like this was a great personal triumph, one that legitimised your stake as a professional, championed and shared with a friend.

Sadly, I know these highs were cut short—in 1870 the Franco-Prussian War and financial necessity wrenched you back to Pennsylvania's airless embrace. Suddenly, the vibrant studios of France were replaced by your family's parlour; the Salon’s rich artistic discourse exchanged for provincial chatter. In June of 1871, your desperation to escape the confines of America was put to paper when you confessed to fellow artist and friend Emily Sartain:

“I am in such low spirits over my prospects that… I should jump at anything in preference to America,”

-(MC to ES, June 7 1871).

Worse still, your efforts in the American market failed. The sale of your work in New York offered “nothing in any degree favourable,” (MC to ES, June 7, 1871), and by July, you abandoned painting entirely, vowing “not to touch a brush” until you could “return to Europe,” (MC to ES, July 10, 1871). This evident frustration underscores your persistent sense of America’s lack, especially when set against your experience of Europe’s centre: where one had demonstrated cultural refinement and artistic success, the United States had revealed itself to be the stage upon which your career was set to die.

I’m therefore certain, Mary, that you would be able to recall in minute detail that day in late 1871 when the Bishop of Pittsburgh’s commission landed in your lap.6 That piece of paper must have felt like more than a practical request for copies from Italy—it was an umbilical cord, tethering you across oceans to the lifeblood of an artistic tradition that had sustained generations before you, nourishing the legitimacy of your own career. "I begin to see daylight," you wrote to Emily on October 21, your pen barely containing your hope as you begged her to join your escape.

What followed was a pilgrimage through Europe’s sacred artistic sites: Parma’s terracotta tang, Andalusia’s golden light, Flanders' meticulous oils, and Paris' glittering galleries. There to stake your claim as a serious artist, as much as you were completing a request, your first triumph came when your painting Two Women Throwing Flowers (Figure 3) was accepted to the Paris Salon of 1872. Then, following the completion of your commission that autumn, your development continued in Spain, where the work of Velázquez had a significant impact on you.

"I think that one learns how to paint here,"

-(MC to ES, Madrid, October 13, 1872).

The clarity that came with these months of study would echo in your own brushwork. In Parma, Correggio's frescoes demonstrated innovative approaches to light and form, and when you reached Madrid, studying Velázquez's works firsthand taught you how to portray ordinary moments with remarkable dignity. In 1873, still studying in Spain, confirmation came once again that you were on the right path when your painting, Torero and Young Girl (Figure 4), was accepted to that years Salon.

It’s evident that, having been denied formal training at institutions like the École des Beaux-Arts, you created your own education through travel—spending hours meticulously studying and copying these masterworks in museums and churches, then implementing what you’ve observed into your own practice, building the foundations of your career.

Your subsequent journey to the Netherlands and Belgium, via the Parisian Salon of 1873, was more than a "jaunt" as you called it (MC to ES, [Antwerp] June 25 1873). Just like your other travels, your “enchantment” with the works of Masters such as Rubens and Rembrandt was a calculated step towards solidifying your professional credibility. But the true gain of this engagement lay in your networking. Through the Tourneys, particularly the self-assured Mrs. Tourney, who "sells her pictures" much to your mother’s amused disbelief, your work would reach Edgar Degas. His legendary remark— ‘Here is someone who feels as I do’ —has been used to mark your entry into the Parisian avant-garde, that place in which you secured your legacy.7

Art historians have since largely focused on your years spent integrated amongst the French Impressionists, analysing your role as an ‘expat’ within the rebellious, masculine world of the Indépendents. This label implies a break from a home country without necessarily crafting a meaningful integration abroad, a kind of ‘once-was-but-no-longer’ of national affiliation. And to an extent, this might seem applicable to you. As with many other artists, success came at a cost. American audiences recoiled at your Impressionist style, refusing to recognise its merit, which ultimately led to you severing your ties with the American colony in Paris.8

But Mary, as we both know, you never renounced your American roots.

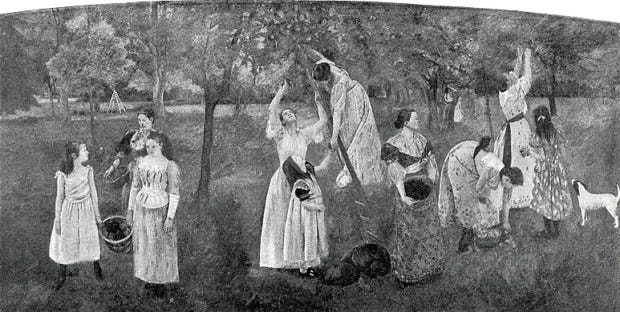

Your eight years of travelling, and fifty years spent living in Paris constituted neither exile nor alienation, but a strategic navigation of a dual belonging. Whilst, yes, you integrated into French society and took up their stylistic approaches, you also cultivated transatlantic friendships, worked with American dealers and collectors, and even after years of snubbing your work, helped U.S. museums acquire French avant-garde art—ensuring your homeland would not remain culturally isolated.9 Even your feminism was distinctly American, supporting women’s suffrage on U.S. soil—as seen in your support of Louise Havemeyer’s 1915 New York suffrage exhibition, and earlier, your production of the Modern Woman mural (Figure 5) for the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition (now lost). As you told Achille Ségard in your first biography:

"I am an American, clearly and frankly American."

-Mary Cassatt, translated from the French original.

These decisions do not show an artist who gave up one part of their identity for another, but exemplify to me someone who strategically utilised their displacement, their dual-associations, as a means of achieving career, political, and personal successes. The label of "expat" therefore does more than just misrepresent you—it erases and neutralises the deliberate utilisation of your dual-peripheral identities: as both an American, and as a woman.

Mary, I believe your experiences are emblematic of a unique intersection of your identity—an American among Europeans, and a woman navigating a world dominated by men. In both ways, you experienced a kind of peripherality, wherein your national affiliations and training, as well as your gender, restricted the means in which you could exercise agency towards achieving your life goals. While I understand why you fiercely resisted being pigeonholed as a ‘female artist', gender still profoundly shaped your career.10

When you began at PAFA in 1860, you were denied access to nude life drawing classes, an essential pillar of training deemed ‘improper’ for women.11 Then in Europe, you were still kept on the gender periphery: unable to access official education at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts, nor leisure in cafes with other creatives because you were a woman, you were forced to find mentors and craft networks via private instruction—an undertaking made easier given the financial support of your family, and their own transnational connections to the cultural elite.12

However supportive they might have been, I know your parents still voiced their concerns for your chosen profession. Your mother, Katherine, frequently tried to steer you to ‘suitable’ subjects like portraits and still-life’s; whilst your father Robert stated he would rather see you dead than have you go to Europe to study art.13 His fears, perhaps stated a little too fiercely, came from concerns for your social wellbeing. To be a woman studying art, especially in the very public spaces of Paris—such as the Louvre, under the stare of gawking tourists—was to risk one's reputation with every brushstroke.14

And then came the greater expectation, that thing that took precedence over any woman’s career—marriage, and eventual maternity, a woman’s true purpose. How exhausting it must have been to hear the same refrain from even well-meaning lips: that art was but a fleeting fancy, that women were naturally inclined towards domesticity, and therefore incapable of greatness.15 One of your biographers, Nancy Mowll Mathews writes that as you and Eliza reached your mid-twenties, skepticism grew about your ability to hold on to your art in the face of a proposal from some “nice young man,” (Mr. SH to EH, 2 March 1863). Did you read the letter Eliza’s father sent? The one that unceremoniously stated this inevitability:

"You will get married and settle down into a good housekeeper like all married women & send off your paints into the [attic]! There is a prediction for you, and one founded upon almost universal experience,” (Mr. SH to EH, 2 March 1863).

Even for someone as headstrong as you, your positionality as a woman—and therefore always experiencing the art world from your gendered periphery—inevitably shaped your experience even in the centre of the art world. When Emily Sartain left Parma for Paris in April 1872, you stayed on to finish your commission, planning to travel to Spain afterwards. But the prospect of going alone unsettled you. You begged Emily to join, but she refused. Still, you took the leap, trusting mutual American friends would meet you. They never came.

Your letters from Madrid betray a deep loneliness, particularly your frustration at the absence of other women. “6 P.M….very tired, & rather lonely,” you wrote, “I don't see any women about, nothing but men.” (MC to ES, [Madrid] October 5, 1872). Desperate for companionship, you tried to lure Emily with Spain’s artistic riches. “I really never in my life experienced such delight in looking at pictures,” you insisted. “No Titiens in Italy are finer, nor Rafaelles either—the Madonna of the fish is most beautiful,” (MC to ES, [Madrid] October 5, 1872). You painted Madrid as a paradise of light and ease, with only a hint of guilt-tripping: “Well, I woke up this morning with the sun shining brightly on this brilliant clean town, a most delicious spring temperature, and if I had only had an artist friend…I think I would have been happy. Indeed Emily, you must come.” (MC to ES, [Madrid] October 27, 1872).

And when persuasion failed, your tone sharpened:

“...you and Mrs. Tolles ought to consider yourselves lucky, for I am here as a sort of pioneer to you two; by the time I have learned by bitter experience how to avoid being cheated, you two will [be] able to profit by it!”

-(MC to ES, [Madrid] October 27, 1872).

Your fiery persistence here only thinly veils a keen loneliness—a foreshadowed rift that would ultimately divide you and Sartain.

This period shows that even as an independent artist, being a woman in Europe meant existing on the margins. Without companionship, the barriers felt heavier, your ambitions clouded by isolation. Your letters reveal not just solitude, but the labor of navigating a world that resisted you. Yet, I see something else: a hard-won freedom. Moving through foreign landscapes, you unknowingly exercised liberties most women could never claim—little familial supervision, away from your own society's censure, just open space for self-invention. This autonomy became the bedrock of your creative identity, allowing you to experience moments of great loneliness.

Here lies the beautiful contradiction: the very identities that excluded you—American, migrant, woman—became your passport to an unprecedented movement. Your dual peripherality, as both a woman and a foreigner, brought difficulties, yes—but it also brought agency. It carved out a space where you could, where you had to, reinvent what it meant to be an artist. Your travels—both solo and with companions—hauling paints, easel, and canvas from atelier to museum to salon, speak to an active fashioning of your legitimacy, and a freedom that many women who remained within their original contexts were not afforded.

“Speak to me of France. Women do not have to fight for recognition here if they do serious work… [for] women should be someone and not something.”

—Mary Cassatt (quoted in a letter from Sara Hallowell to Bertha Palma, 6 February 1894)

Your letters, when one reads ‘between the lines’, thus reveal a remarkable freedom of movement and autonomy. On your first expedition (1866-1870), you visited artists’ studios in Villiers-le-Bel with both male and female friends, and the Louvre became a “second Academy,” the only place where you and Eliza could receive male companions, as your lodgings forbade it.16 When Eliza returned to America in late 1868, you remained—a single woman traveling and working largely independently, an unusual choice for someone of your class, made even more daring by your pursuit of a professional art career.

One of your first trips after Eliza’s departure was the Swiss Alps with a friend from Philadelphia—someone who “calls herself a painter,” though you, ever direct, admitted, “she is only an amateur and you must know we professionals despise amateurs…” (MC to Lois Cassatt, [Savoie] 1 August 1869). Still, you “roughed it most artistically” with her, hauling your paints and papers through snow and stone, trekking for twelve hours to catch a view of Mont Blanc and the St. Bernard. “We waded up to our ankles in snow,” you wrote, “but were rewarded by a magnificent view.” These were not the leisurely travels of a tourist, but the determined passages of a working artist, carving out legitimacy with every step.

After this, you journeyed alone to Rome in 1870, studying under Charles Bellay and refining your Alpine studies into your second Salon triumph, Contadina di Fabriano; Val Sesia (Piedmont) (now lost). Your next pilgrimmage (1871-1874) followed a similar pattern. I believe that, because you were an ‘foreigner’, you moved freely through and between Italy, Spain, and France, taking up opportunities as they came to you.

Undoubtedly your class affiliations aided this experience. Your parents, however nervous they might have been about the implications of your profession, continued to support you—though at times you had to pull on their heartstrings, a tug-of-war between your ambitions and their dampening of your expectations.

“Mother wrote to me that Father did not wish to send me a large bill but little and often, as he was afraid, but when he hears that I came on without waiting for money I have no doubt he will be in an awful state of mind,”

-(MC to ES, [Madrid] 5 October 1872).

Mary, am I right in claiming that you didn’t necessarily rely on the income of selling your artworks, though it certainly helped: “… the Bishop has paid me!!! … I assure you I was glad to get the money for Mother absolutely refused to pay models this summer, considering them an unnecessary expense,” (MC to ES, [Antwerp] 25 June 1873). It was evidently though still of importance to both yourself and your young artist friends, writing to Eliza with emphasis, “Have you been exhibiting & above all things selling?” (MC to ES, [France] August 17 1869). However, I think it was the legitimacy that came with being an artist who sells, and sells well and often, that drove your focus on this aspect of the profession.

This navigation of the domestic and public, of what it means to be a woman, and what it means to be an artist, takes form throughout your oeuvre.

Mary, I believe it was these early years of travel, experimentation, and—most importantly—the freedom to choose, that carried you toward the place where your legacy would take root: Paris. Each step along the way developed your skills, knowledge, experience, and networks—everything the art world was reluctant to grant someone who was both a woman and not European. But you didn’t let that stop you. Freed from the constraints of national allegiance and domestic expectation, you began to navigate both public and private life increasingly on your own terms. This freedom—paradoxically born of displacement—became the fuel for your artistic success…

*Code for in-text citations of letters:

MC = Mary Cassatt

EH = Eliza Haldeman

Mr. SH = Mr. Samuel Haldeman

Mrs. SH = Mrs. Samuel Haldeman

ES = Emily Sartain

PAFA = Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts

Life writings in this case refers to letters made available by the 1984 Mathews publication Mary Cassatt and her Circle: Selected Letters. To this authors understanding, no archive of her letters have been digitised. The focus on this research was on Cassatt’s initial years travelling in Europe before she settled in Paris. This author has attempted to critically consider the intended audience of the letters sent, as well as the person writing them.

Nancy Mowll Mathews, Mary Cassatt: A Life. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1998, 15.

Mathews, Mary Cassatt: A Life, 18.

Ibid, vii and 26.

Ibid, 15.

Mary Cassatt, Cassatt and Her Circle : Selected Letters. Edited by Nancy Mowll Mathews. First edition. New York: Abbeville Press, 1984, 66

Cassatt, Cassatt and Her Circle : Selected Letters, 126.

Mathews, Mary Cassatt: A Life, 49.

Ibid, 267.

Ibid, 308.

Cassatt, Cassatt and Her Circle : Selected Letters, 17.

Mathews, Mary Cassatt: A Life, 10.

Ibid, 36.

Ibid, 34.

Ibid, 58.

This was beautiful!